thenumerateninny.com

Natterings of a Woman in STEM

Why I will never say ‘I’m not a racist’

I will never say ‘I’m not a racist’.

Like other human oddities, the reason for this can be found in my formative years. Let me tell you the story…

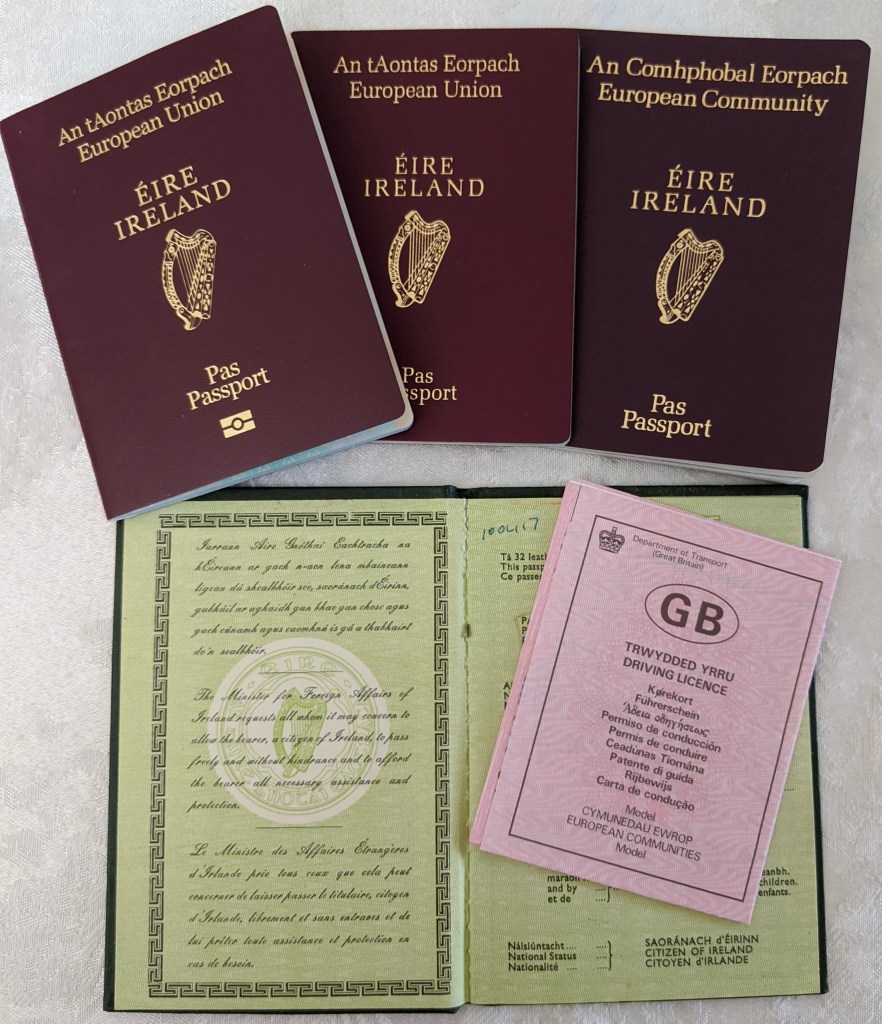

Once upon a time, there was a young engineer who lived in Britain. She traveled a lot for work, and studied explosions and fires for a living. Most shockingly of all, she was an Irish national.

It is quite possible that she fit a profile, a profile that was considered very dangerous in the 1990s.

This profile meant that her near-weekly trip through Heathrow Airport involved a bag search and a body pat-down. Unfortunately, her English colleagues never believed she needed extra time to get through airport security, and at least one expensive flight was missed for that reason. (Believe me, this is not something you want to explain on your expense report.)

Being profiled engendered odd behavior: When the young engineer traveled with tools, those metal objects proved to be a little too fishy for the comfort of airport security. She soon learnt it was best to freely offer up her baggage for examination rather than be pursued through the airport for that purpose. In fact, she adopted the habit of contacting security during check-in, to get the whole business out of the way as efficiently as possible.

Being profiled damaged professional relationships in unimaginable ways: Once the Irish engineer had to travel with the prissiest of men. At the last minute, she realized she had forgotten to pack sanitary supplies. Since there was nowhere in her overstuffed baggage for an entire box of necessities, she tucked individual sanitary pads into every nook and cranny of her luggage. At Heathrow, the ever-so-predictable request to examine her bag was made. When security pulled open the zipper of her luggage, sanitary products flew out across the counter. Everyone scrambled to catch the items as they fell back to earth. The engineer’s poor, poor prudish colleague could not speak to her for days.

Being profiled destroyed everyone’s peace of mind: On another occasion, the engineer had to depart from a regional airport in the north of England. A severe delay in departure tested everyone’s patience. At last, the small plane was ready for boarding. The police constable overseeing the embarkation pricked his ears at the sound of an Irish accent. He required the young woman to stop and fill out a Prevention of Terrorism form. (At that time, Irish people in the UK had to fill out this form if they sneezed, or walked, or engaged in other dubious activities, like standing in airports). Her fellow travelers, delayed yet again, were deeply disgruntled.

“What’s going on?” a man behind her asked, irritated.

“She’s a terrorist,” someone else replied, deadpan.

Dogged by distrust, she boarded the little plane. Happily (or is it sadly), she had no opportunity to engage in her intended criminality (stealing the airline magazine). There were thirty sets of eyes watching her every move.

And this ridiculousness was bearable.

Why?

Was it because she had been harassed in such a mannerly fashion? (Police constables were terribly polite back then.) Was it because a short myopic young woman could look up at the blurry face of authority and think that, if only it came into focus, it might be friendly?

No. Those were not the reasons the situation was bearable.

It was bearable because of the dichotomy.

While every police force in the UK was stalking the Irish engineer’s movements, the general population treated her as an insider.

“I have a problem with immigrants who don’t make an effort to fit in,” she would be told, confidentially.

“Oh, like me?” she would reply, because she never made any effort to fit in.

Flustered, “No, I didn’t mean you.”

The speaker’s eyes would stray to another person, a fellow-countryman, someone who had been born locally, shared the same education and accent as the speaker, and had regrettably adopted the same taste in dress. However, the Briton being eyeballed looked very much like a grandparent who had immigrated from the Caribbean, or the Indian subcontinent, or some other place that was not Europe.

“Oh, he’s not an immigrant,” the Irish engineer would declare disingenuously to her English acquaintance. “He’s from Essex.”

Her companion would then patronizingly explain how his statement should have been interpreted, because – clearly – she did not understand what team she was supposed to be on. The explanation usually started with the words:

“I’m not a racist…”

So, the Irish engineer started a semi-scientific study. She listened for the words ‘I’m not a racist’ and took note of what accompanied those words. The results of her thirty-year, academically indefensible, study are as follows:

1. Most of the time, the first word following ‘I’m not a racist’ is ‘but‘.

2. At least half of the time, the words after ‘I’m not a racist’ are blatantly racist.

3. When the words after ‘I’m not a racist’ are not blatantly racist, they are subtly racist.

To be fair, I think the words ‘I’m not a racist’ actually mean ‘I’m trying not to be a racist, but I’m not sure of how to go about it’.

We are human; we often fail at difficult things. So, I accept that changing the way you think is incredibly hard.

But still, I will never say ‘I’m not a racist’.

Here is a link to a popular poem about being Irish. Unfortunately, the first line is not factual:

Follow The Numerate Ninny on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn or at: https://thenumerateninny.com/

Find my books on all Amazon platforms.

Well said, Amanda. A very interesting perspective.

Can’t help wondering why we stood in front of the bobbies. Bernadette

LikeLike

Well said, Amanda. A very interesting perspective. Can’t help wondering why we stood directly in front of the bobbies? Bernadette

LikeLike

We were tourists!

LikeLike